RBC Wealth Management: The economic impact of Russia's invasion of Ukraine

The Russia-Ukraine war is transforming the European economic and geopolitical order. Peace can no longer be taken for granted. While a dark cloud has descended over the continent today, we believe opportunities in the region remain.

Long-term implications

No matter what the outcome of the war may be, a changed EU will emerge in a new era. We highlight key areas of transformation, including a move towards more regional cohesiveness; a revving up of the green energy transition; the absorption of the large influx of refugees; and a relaxation of attitudes towards fiscal discipline.

Greater cohesion

The bloc surprised many by the decisiveness displayed in swiftly imposing a punishing package of sanctions against Russian oligarchs and institutions. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has galvanised the EU to open its coffers, including providing Ukraine with €1.2 billion in financial and humanitarian aid and €450 million of military assistance. EU leaders have also accepted Ukraine’s application for EU membership—though the process may well take another 10 years.

The conflict spurred a radical change in Germany’s defence policy almost overnight. Chancellor Olaf Scholz approving the export of lethal weapons to a conflict zone for the first time since World War II is a pivotal action that could encourage further EU cohesion.

The war has also dulled the appeal of eurosceptic parties, both on the far right and far left, which often cited Russian President Vladimir Putin as a role model. This likely reduces the risk of an anti-EU government being elected in France or Italy (elections to be held in April 2022 and in 2024, respectively), and probably positions the bloc more firmly in the center.

Yet we shouldn’t expect complete cohesion on all matters. For one, unlike trade policy where the EU can legislate like a sovereign government, EU foreign and security policy is intergovernmental, so the EU can only act when all members agree. The threat posed by the invasion of Ukraine was so menacing that all members swiftly agreed on a course of action. Had the threat been somewhat less ominous, we believe the EU would have reverted to building a compromise among all members, a process that likely would have prevented it from acting quickly. In other words, as long as the veto system is in place, the EU continues to run the risk of being bogged down in lengthy negotiations among its 27 member states.

French President Emmanuel Macron has been arguing that the time has come for an EU-wide defence policy. This would require amending the EU treaty to do away with the veto system, a move many members remain reluctant to support.

Having said that, fresh on the heels of the success of the EU’s coordinated response to COVID-19, the threat of menacing external aggression will likely shift the balance towards a greater tolerance for EU-level decisions, as opposed to at the national level, as EU member states reflect on common interests and objectives.

The adoption by EU foreign and defence ministers on March 21, 2022 of a “Strategic Compass”—a plan to strengthen the EU’s security and defence policy over the next decade—goes some way to better coordinate EU members in this matter.

Revving up the green transition

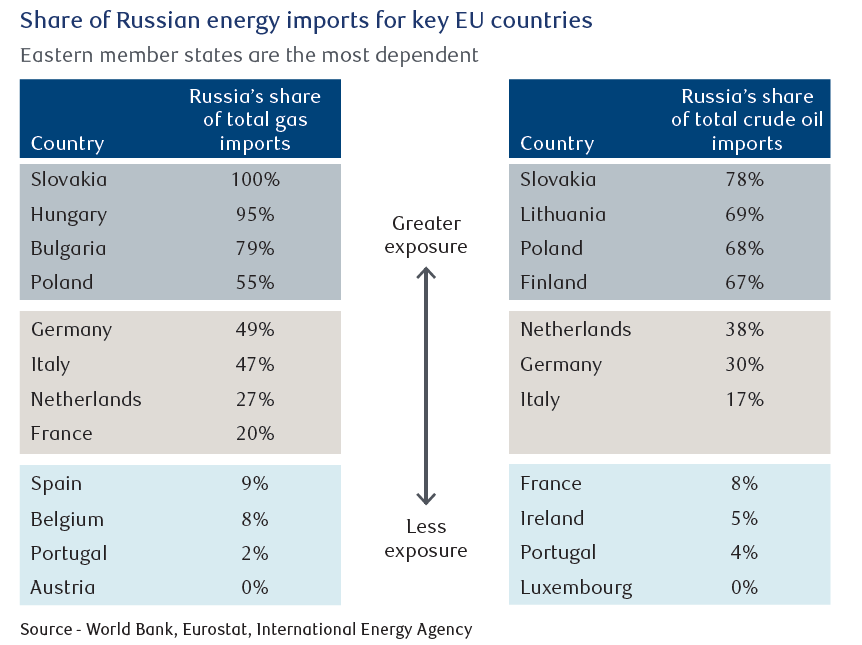

Because Europe’s heavy dependence on Russian energy is clearly undesirable, the European Commission has proposed a three-step plan, REPowerEU, to reduce it. In contrast to the U.S., which has banned Russian oil imports, the EU’s plan involves a more gradual approach to wean itself off Russian energy.

REPowerEU calls for reducing Russian energy imports by 65 percent over the remainder of this year and completely before 2030. This will require long-term investments in renewables and energy efficiency, as well as short-term measures such as purchasing non-Russian oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and coal; greater use of nuclear energy; and reducing energy demand by, for instance, encouraging consumers to lower home temperatures by one percent. The plan also aims to increase gas reserves to 90 percent of capacity, versus 30 percent currently, by Oct. 1 each year so as to improve the system’s resiliency.

It is up to each member state to decide how these goals will be reached. For example, Germany’s initial response was to bring forward its target of 100 percent renewable energy by more than a decade to 2035, a move which requires a €200 billion commitment to almost triple onshore wind and solar capacity, and more than double offshore wind. In the short term, Germany is considering prolonging the use of coal beyond 2030, and it announced plans to build two LNG terminals whilst bolstering gas and coal storage.

Many wonder if the new imperative of replacing Russian energy imports means abandoning the net-zero goal as the EU will need to reopen coal plants and rely on nuclear energy for a longer period of time. But the situation is not so clear cut, in our view.

Bloomberg estimates that burning additional coal instead of Russian gas would increase the EU’s carbon emissions by about eight percent. But it points out that as Europe isn’t planning to construct new coal power plants as part of its response to the crisis, any pollution created by new coal and oil imports could be offset by green replacements that will likely be scaled up. Still, boosting additional sources of gas, which European homes rely on for heat, and building the required infrastructure, such as the two proposed German LNG terminals, will lock in gas consumption for decades.

Most importantly, the green transition has moved up the agenda, from being an environmental issue, to becoming a security matter.

Absorbing the influx of refugees

Ukrainian refugees could have a significant effect on the rest of Europe. Already, some three million people have fled Ukraine. The UN’s estimate of four million refugees by the end of the conflict is very likely to be surpassed.

Eric Lascelles, chief economist at RBC Global Asset Management Inc., points out that some will return when the war is over, especially since most Ukrainian men remain in the country, though many refugees will not, either because of the destruction to Ukraine or the economic opportunities that wealthier European nations can offer.

He estimates the EU population could well grow by at least one percent in short order. Such migrations are not friction-free, as demonstrated in 2014–2015 when many refugees arrived in Europe from the Middle East and Africa. But as the migrant population settles and gains employment, Lascelles sees the opportunity for a period of faster eurozone economic growth that could last for several years.

In the shorter term, absorbing such an influx of people will be challenging. The welcoming effort so far is largely privately-driven. Should the conflict drag on for an extended period, EU leaders will have to address how to best integrate refugees into society and the economy.

Fiscal relaxation

Attitudes towards fiscal support are evolving. German Finance Minister Christian Lindner is now advocating for increased defence spending representing 2.7 percent of the country’s GDP, with possible increases thereafter. A more constructive tone from Germany, long a fiscal hawk, could suggest the outcome of the EU’s review of fiscal policy, a key topic under discussion this year, may allow governments to run budget deficits at an adequate level as opposed to the straightjacket of fiscal rectitude. A more relaxed fiscal stance could underpin growth.

Lascelles notes there is scope for this approach, as fiscal deficits and public debt in Europe are relatively smaller than those in the U.S.

Spending will take many forms. The EU and its member states are looking to protect lower-income households and vulnerable small and medium-sized enterprises from soaring energy prices. We already saw some measures taken last autumn when prices started to spike. But as prices will more than likely remain elevated for some time, national governments, such as France and Germany, are looking to subsidise energy costs or remove gas taxes temporarily. So far, such measures amount to under one percent of member state GDPs.

Spending on energy infrastructure, such as the two German LNG terminals, is another key area of expenditure. Germany’s pledge to meet NATO’s target for defence spending of two percent of GDP led other member countries to announce similar long-term commitments, though not all will be able to follow suit given other spending requirements.

EU-wide defence spending is needed to fill capability gaps so as to improve military readiness, according to the Centre for European Reform, a think tank that focuses on European integration. At an informal summit in Versailles on March 10–11, EU heads of state agreed to a “substantial” increase in defence spending.

The debate has started as to how this will be financed. At the summit, EU national leaders agreed on the priorities of defence, energy, and economic resilience and discussed a spending programme of up to €2 trillion.

Macron put forward the idea of more joint EU borrowing. There was a general recognition that the €750 billion recovery fund to help member countries weather the pandemic had been productive by providing fiscal flexibility, enabling the EU to coordinate loans and transfers, and allowing for the issuance of debt at the EU level. In effect, the recovery fund was seen as a prototype for the response to the current crisis.

The discussion is evolving towards whether there is scope to use the recovery fund to underpin new initiatives as not all funds have been released—some member states perceive this option as more prudent. Over time, more joint debt issuance is likely, in our view. We think the probable re-election of Macron in April, as expected by a wide array of pollsters, could speed up this process.

The summit launched a dynamic framework for the March meeting of the EU Council and the forthcoming gathering in June where more details will be discussed.

Short-term pain

Elevated energy costs, supply chain disruptions, and reduced demand as the uncertainty of the war dampens consumer spending will all conspire to dent the European economic recovery in 2022, in our opinion. Thankfully, this unwelcome turn comes after the region’s economy started the year on a relatively strong footing, benefiting from the lifting of COVID-19-induced restrictions.

Nevertheless, economic forecasts are being revised down. Lascelles recently further fine-tuned his 2022 projection for the eurozone’s GDP growth to 2.5 percent, down from 3.8 percent early this year. More adjustments are likely in light of the rapidly evolving situation.

The recent decline in energy prices could give the region some respite and we are also watching for potential fiscal spending announcements, as such injections could lift growth. But the impact of the war on consumer and business sentiment, and whether energy-intensive companies have to cut output should there be further restrictions on Russian energy—be they imposed by the EU or Russia turning off the taps—could weigh further on economic activity.

Lascelles looks for inflation to peak higher this year as a result of the conflict, at around eight percent year over year. Worried about such a high level, and the impact of the war on economic growth, the European Central Bank (ECB) is angling for some flexibility. While it announced it will accelerate the reduction of its asset purchase programme, now aiming to end it in Q3, the ECB also suggested it could increase bond buying again if circumstances warranted. Furthermore, the ECB’s statement after the March 10 policy meeting omitted the comment that rates could rise shortly after the end of asset purchases. RBC Capital Markets expects the ECB won’t increase interest rates before 2023.

Stock market implications

In the medium term we expect fiscal spending should underpin growth, while over the long term the EU could eventually emerge from the conflict with stronger institutions. But the short-term outlook is nevertheless more complex than it was earlier this year.

The MSCI Europe ex UK Index is down more than 10 percent in local currency terms since its January high, leaving the index to trade at 14.3x the forward consensus earnings estimate, a steeper-than-average discount to the U.S. on a sector-neutral basis. This low level suggests that the reductions in growth forecasts largely appear to be factored into the current valuation.

Yet we think it is prudent to downgrade European equities to Market Weight from Overweight given it is a market with a relatively high proportion of cyclicals.

We still believe there is an attractive opportunity in stocks related to the green energy transition. This remains very much a priority for the EU, and, if anything, it is now seen as a security issue and not just an environmental matter. Europe continues to be a leader in this area and we think compelling opportunities can be found after the recent correction.

.png)

.jpg)